For years, Jonathan Morton and I have been thinking and talking about Richard de Fournival’s Bestiaire d’amours (Bestiary of Love). During the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 we met for 90 minutes, four times a week over Zoom, with the same document open in OneDrive, to discuss this puzzling work and write down some thoughts. A much-honed version of these thoughts have now been published as a book: Performing Desire: Knowledge, Self, and Other in Richard de Fournival’s Bestiaire d’amours.

Writing an entire monograph with another scholar is a fairly unusual thing to do in the humanities, and our process felt pretty modern. It could not have happened without the ability for us both to be working on the same document in real time while also being in dialogue over a video call.

For me, as well as being a really fun and companionable way of keeping in touch during the strange social circumstances of a global pandemic, it was an interesting insight into our different ways of working, thinking, and writing.

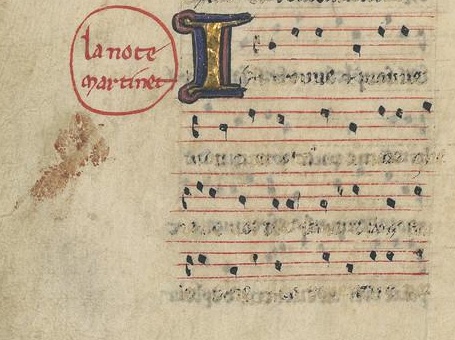

The nicest thing about the finished book is that we were able to include so many colour images. The book is available by clicking on the cover image above, but if you want to listen to an AI generated podcast giving a sense of its contents, I’ve uploaded one prepared by NotebookLM. You’ll have to forgive its inability to pronounce the French word ‘je’ (which comes out as jay).

We explore Richard de Fournival’s thirteenth-century text, the Bestiaire d’amours, which presents itself as a bestiary but functions as a cynical and parodic seduction attempt using animal lore. The book analyses the hybrid nature of Richard’s work, discussing how it stages a trial of textuality and blurs the lines between written and oral performance, often employing scholastic methods and lyric subtexts to undermine its own claims to authority. Key themes examined include the je-persona’s unreliable voice, the text’s confused epistemology (especially regarding vision, hearing, and the unreliable nature of resemblance), and the work’s commentary on place, bodies, and desire. We also discuss the work’s generation of responses of various kinds, highlighting its importance for the literary investigation of sexuality and textuality in the later Middle Ages.